Into the Bibby Zone

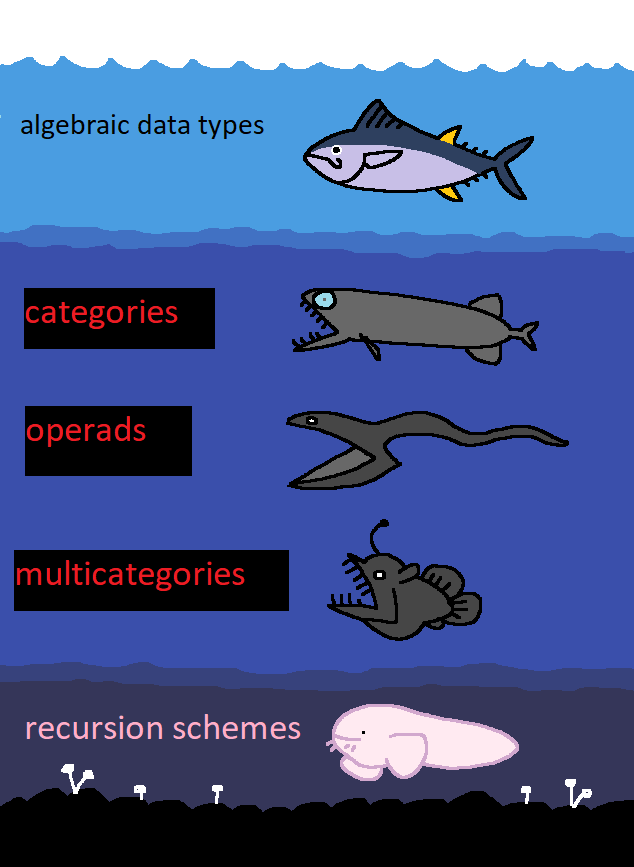

As I've recently announced on Twitter, I'm starting a new blog series at the intersection of type theory, category theory, and functional programming.

The correspondence between lambda calculus and bicartesian closed categories is well known, and functional programmers have been using it to great extent. What is less widely known is how to extend this correspondence beyond just lambda calculi. In other words:

- Given an arbitrary DSL, how can we begin thinking about its categorical semantics?

- Given a category-theoretic structure, how can we give it a practical programming syntax?

Our approach to this will be entirely algebraic (for a very general notion of 'algebraic'). We will represent our syntax using an inductive type, our semantics as an algebra over the type, and our interpreter as a fold connecting the two.

This approach is remarkably scalable. We will see how categories, multicategories, bicategories, and double categories can be all be represented as (indexed) functors over an appropriately chosen category. Using tools from recursion schemes, this will give us generic evaluators for a very wide range of structures.

On the language side, we will start with combinators and build up to simply typed, polymorphic, and dependently-typed languages. At each step we will implement an interpreter between the language syntax and its categorical semantics.

We will use Idris2 as our language, but write our code in a style accessible to Haskell programmers. (Most of the code in the first part of the series should be translatable to Haskell too.)

A free category over Idris types

To start, let's retrace some familiar ground and look at a typed combinator language for bicartesian closed categories. We will interpret our combinator language into an arbitrary BCC, then show how to translate from the simply typed lambda calculus into combinators in the next blog post.

These first two blog posts are meant as a high level introduction to the basic tools and methodology that we'll be using through the series, and we will revisit these ideas step-by-step in subsequent posts.

You can find the full code for this post here.

We'll start with a typical representation of free categories in Haskell - a free category over functions.

data Path : (g : Type -> Type -> Type) -> Type -> Type -> Type where

Id : Path g a a

Cons : g b c -> Path g a b -> Path g a c The first parameter 'g' corresponds to some type of Idris functions. 'a' and 'b' then correspond to the source and target types of the function, Id is the identity function, and Comp is a formal composite of functions.

In our case we will use the set of Idris functions

Idr : Type -> Type -> Type

Idr a b = a -> b But we can also instantiate it with various useful categories from functional programming, such as Kleisli categories over a monad.

Kleisli : (Type -> Type) -> Type -> Type -> Type

Kleisli m a b = a -> m b This representation isn't as general as it could be, though.

And since we have access to dependent types, let's formulate what it means to be a free category in general, not just free over Idris types.

Graph : Type -> Type

Graph obj = obj -> obj -> Type The definition of a free category stays the same, but our type becomes more informative

data Path : {obj : Type} -> Graph obj -> Graph obj where

Id : {a : obj} -> Path g a a

Cons : {a, b, c : obj} -> g b c -> Path g a b -> Path g a c A term of a free category is nothing other than a path constructed from composing individual edges of a graph.

You might notice the correspondence between this type, and that of Lists

data List : Type -> Type where

Nil : List a

(::) : a -> List a -> List a Which motivates the idea that a category is a typed monoid.

The evaluator for a free category is very similar to a fold for a list, except that we replace each edge with a function rather than an element.

eval : Path Idr a b -> Idr a b

eval Id = id

eval (Cons f g) = f . (eval g)The Free Bicartesian Closed Category over Types

We will now go from a free category to a free category with products, coproducts, and exponentials. For readers new to category theory, we will go through each of these properties in more granular detail in subsequent blog posts. But for now we will define them all in one go.

We can then define our bicartesian category over types as:

data BCC : Graph Type -> Graph Type where

-- Embedding a primitive is now a separate operation

Prim : k a b -> BCC k a b

-- Identity arrow: a → a

Id : {a : Type} -> BCC p a a

-- Composition of arrows: (b → c) → (a → b) → (a → c)

Comp : {a, b, c : Type} -> BCC k b c -> BCC k a b -> BCC k a c

-- Product introduction: (a → b) → (a → c) → (a → (b * c))

ProdI : {a, b, c : Type} -> BCC k a b -> BCC k a c

-> BCC k a (b, c)

-- First projection: (a * b) → a

Fst : {a, b : Type} -> BCC k (a, b) a

-- Second projection: (a * b) → b

Snd : {a, b : Type} -> BCC k (a, b) b

-- Coproduct introduction: (b → a) → (c → a) → (b + c → a)

CoprodI : {a, b, c : Type} -> BCC k b a -> BCC k c a

-> BCC k (Either b c) a

-- Left injection: a → (a + b)

InL : {a, b : Type} -> BCC k a (Either a b)

-- Right injection: b → (a + b)

InR : {a, b : Type} -> BCC k b (Either a b)

-- Exponential elimination:

Apply : {a, b : Type} -> BCC k ((a -> b), a) b

-- Currying: (a * b → c) → (a → (b ⇨ c))

Curry : {a, b, c : Type} -> BCC k (a, b) c -> BCC k a (b -> c)

-- Uncurrying: (a → (b ⇨ c)) → (a * b → c)

Uncurry : {a, b, c : Type} -> BCC k a (b -> c) -> BCC k (a, b) c(One important caveat is that our data-type now represents a free f-algebra rather than a free category in the strict sense. We'll talk more about the distinction in future posts, but for now I'll abuse notation and keep calling both concepts by the same name.)

Defining an evaluator is as simple as it was before, we just match each constructor to the corresponding Idris function

eval : BCC Idr a b -> Idr a b

eval (Prim f) = f

eval Id = id

eval (Comp f g) = (eval f) . (eval g)

eval (ProdI f g) = \c => ((eval f) c, (eval g) c)

eval Fst = fst

eval Snd = snd

eval (CoprodI f g) = \c => case c of

Left l => (eval f) l

Right r => (eval g) r

eval InL = Left

eval InR = Right

eval Apply = uncurry apply

eval (Curry f) = curry $ eval f

eval (Uncurry f) = uncurry $ eval f Since we'd like to work with more general categories, let's define a record for storing our evaluator. If we were working in Haskell, we'd be using a typeclass here.

record Category (g: Graph Type) where

constructor MkCat

id : {a : Type} -> g a a

comp : {a, b, c : Type} -> g b c -> g a b -> g a c

prod : {a, b, c : Type} -> g c a -> g c b -> g c (a, b)

fst : {a, b : Type} -> g (a, b) a

snd : {a, b : Type} -> g (a, b) b

coprod : {a, b, c : Type} -> g a c -> g b c -> g (Either a b) c

left : {a, b : Type} -> g a (Either a b)

right : {a, b : Type} -> g b (Either a b)

apply : {a, b : Type} -> g (a -> b, a) b

curry : {a, b, c : Type} -> g (a, b) c -> g a (b -> c)

uncurry : {a, b, c : Type} -> g a (b -> c) -> g (a, b) c We adjust our evaluator accordingly to use the new record type:

eval' : Category g -> BCC g s t -> g s t

eval' alg (Prim f) = f

eval' alg Id = alg.id

eval' alg (Comp f g) = alg.comp (eval' alg f) (eval' alg g)

eval' alg (ProdI f g) = alg.prod (eval' alg f) (eval' alg g)

eval' alg Fst = alg.fst

eval' alg Snd = alg.snd

eval' alg (CoprodI f g) = alg.coprod (eval' alg f) (eval' alg g)

eval' alg InL = alg.left

eval' alg InR = alg.right

eval' alg Apply = alg.apply

eval' alg (Curry f) = alg.curry (eval' alg f)

eval' alg (Uncurry f) = alg.uncurry (eval' alg f)Our new evaluator simply matches each construct with the corresponding record. Writing out all of these evaluators can become tiresome after a while, and indeed, in a few posts we will see how to do this entirely generically using recursion schemes.

As an example, let's create a record that packages up our earlier definition of the category of Idris functions.

IdrCat : Category Idr

IdrCat = MkCat

id

(.)

(\f, g, c => (f c, g c))

fst

snd

(\f, g, c => case c of

Left l => f l

Right r => g r)

Left

Right

(uncurry apply)

curry

uncurryWe could also instantiate our record with a few choices of categories, such as

-- Cokleisli category of a comonad

Cokleisli : (Type -> Type) -> Type -> Type -> Type

Cokleisli m a b = m a -> b

-- A static effect category over an applicative functor

StaticArrow : (Type -> Type) -> Type -> Type -> Type

StaticArrow f a b = f (a -> b)

-- Freyd category of an arrow

Freyd : (Type -> Type -> Type) -> Type -> Type -> Type

Freyd g a b = g a bIn general, it's rare that any of these constructions preserve all of our underlying structure (products, coproducts, exponentials), but we can always mix and match the syntax as needed.

Free Bicartesian Categories in General

Finally, let's step away from the category of Idris types and define a free bicartesian closed category in general.

Since we can't reuse Idris types, we now need to define a separate datatype for our type universe.

data Ty : Type where

Unit : Ty

Prod : Ty -> Ty -> Ty

Sum : Ty -> Ty -> Ty

Exp : Ty -> Ty -> Ty

N : TyAnd let's define type synonyms for them too

infixr 5 ~>

(~>) : Ty -> Ty -> Ty

(~>) = Exp

infixr 5 :*:

(:*:) : Ty -> Ty -> Ty

(:*:) = Prod

infixr 5 :+:

(:+:) : Ty -> Ty -> Ty

(:+:) = Sum Defining the free BCC is just as before, but whereas we previously defined it over functions of inbuilt types, we now define it over a graph of our new type universe Ty.

data Comb : Graph Ty -> Graph Ty where

-- Primitives

Prim : k a b -> Comb k a b

-- Identity arrow: a → a

Id : {a : Ty} -> Comb p a a

-- Composition of arrows: (b → c) → (a → b) → (a → c)

Comp : {a, b, c : Ty} -> Comb k b c -> Comb k a b -> Comb k a c

-- Product introduction: (a → b) → (a → c) → (a → (b * c))

ProdI : {a, b, c : Ty} -> Comb k a b -> Comb k a c

-> Comb k a (b :*: c)

-- First projection: (a * b) → a

Fst : {a, b : Ty} -> Comb k (a :*: b) a

-- Second projection: (a * b) → b

Snd : {a, b : Ty} -> Comb k (a :*: b) b

-- Coproduct introduction: (b → a) → (c → a) → (b + c → a)

CoprodI : {a, b, c : Ty} -> Comb k b a -> Comb k c a

-> Comb k (b :+: c) a

-- Left injection: a → (a + b)

InL : {a, b : Ty} -> Comb k a (a :+: b)

-- Right injection: b → (a + b)

InR : {a, b : Ty} -> Comb k b (a :+: b)

-- Exponential elimination:

Apply : {a, b : Ty} -> Comb k ((a ~> b) :*: a) b

-- Currying: (a * b → c) → (a → (b ⇨ c))

Curry : {a, b, c : Ty} -> Comb k (a :*: b) c -> Comb k a (b ~> c)

-- Uncurrying: (a → (b ⇨ c)) → (a * b → c)

Uncurry : {a, b, c : Ty} -> Comb k a (b ~> c) -> Comb k (a :*: b) cThe main difference from before is that our primitives are no longer a simple embedding of Idris functions. Now we need a separate type for representing them. As an example, let's use the generators of a monoid over some base type:

data Prim : Ty -> Ty -> Type where

-- Unit

Z : Prim Unit Base

-- Multiplication

Mult : (Prod Base Base) BaseMost of our remaining definition stays exactly the same! This will become a running theme in this series, where adding extra generality will give us more power without too much extra complexity.

We can recover our earlier evaluator once we provide an interpretation of our type universe into Idris types

evalTy : Ty -> Type

evalTy U = Unit

evalTy (Exp t1 t2) = (evalTy t1) -> (evalTy t2)

evalTy (Prod t1 t2) = (evalTy t1, evalTy t2)

evalTy (Sum t1 t2) = Either (evalTy t1) (evalTy t2)

-- We'll interpret our base type as the type of naturals

evalTy N = Nat We can then define an evaluator. We'll start by interpreting in Idris functions, then generalise to records again. First we'll need to interpret the type of primitives.

evalPrims : Prims ty1 ty2 -> Idr (evalTy ty1) (evalTy ty2)

evalPrims Z = \() => 0

evalPrims Mult = uncurry (+)Then we'll write out interpreter for the rest of terms. We could have parametrised our eval function by evalPrims, but for now we'll keep things simple.

eval : Comb Prims ty1 ty2 -> Idr (evalTy ty1) (evalTy ty2)

eval (Prim f) = evalPrims f

eval Id = id

eval (Comp f g) = (eval f) . (eval g)

eval (ProdI f g) = \c => ((eval f) c, (eval g) c)

eval Fst = fst

eval Snd = snd

eval (CoprodI f g) = \c => case c of

Left l => (eval f) l

Right r => (eval g) r

eval InL = Left

eval InR = Right

eval Apply = uncurry apply

eval (Curry f) = curry $ eval f

eval (Uncurry f) = uncurry $ eval f The main thing that's changed is that now instead of evaluating into Idris functions directly, we must first evaluate our source and target types. Thanks to the magic of dependent types, our compiler knows what the types of our evaluated combinators should be, so it's really hard to make a mistake here. This is something that will become invaluable once we start working with languages with more interesting notions of variable context.

Once again we would like to generalise from evaluating our

combinators into the category of Idris types to evaluating into

morphisms of an arbitrary category. Our types are now evaluated into

objects ty : Ty -> obj and our combinators are evaluated

into morphisms, whose source and target are calculated by first

evaluating the objects

Comb _ ty1 ty2 -> c (ty s) (ty t)

We'll package up the evaluator for objects in a more modular way later, but for now let's just stick the entire thing into our definition of a BCC:

record BCC {obj: Type} (g: Graph obj) where

constructor MkCat

-- evaluator for objects

ty : Ty -> obj

-- evaluator for morphisms

id : {a : Ty} -> g (ty a) (ty a)

comp : {a, b, c : Ty} -> g (ty b) (ty c) -> g (ty a) (ty b)

-> g (ty a) (ty c)

prod : {a, b, c : Ty} -> g (ty c) (ty a) -> g (ty c) (ty b)

-> g (ty c) (ty (a :*: b))

fst : {a, b : Ty} -> g (ty (a :*: b)) (ty a)

snd : {a, b : Ty} -> g (ty (a :*: b)) (ty b)

coprod : {a, b, c : Ty} -> g (ty a) (ty c) -> g (ty b) (ty c)

-> g (ty (a :+: b)) (ty c)

left : {a, b : Ty} -> g (ty a) (ty (a :+: b))

right : {a, b : Ty} -> g (ty b) (ty (a :+: b))

apply : {a, b : Ty} -> g (ty ((a ~> b) :*: a)) (ty b)

curry : {a, b, c : Ty} -> g (ty (a :*: b)) (ty c) -> g (ty a) (ty (b ~> c))

uncurry : {a, b, c : Ty} -> g (ty a) (ty (b ~> c)) -> g (ty (a :*: b)) (ty c)

-- evaluator for primitives

e : g (ty Unit) (ty N)

mult : g (ty (N :*: N)) (ty N)We've also included an evaluator for our primitives, in this case the multiplication and unit of a monoid.

Our final evaluator is then:

eval' : (bcc : BCC g) -> Comb Prims ty1 ty2 -> g (bcc.ty ty1) (bcc.ty ty2)

eval' alg (Prim Z) = alg.e

eval' alg (Prim Mult) = alg.mult

eval' alg Id = alg.id

eval' alg (Comp f g) = alg.comp (eval' alg f) (eval' alg g)

eval' alg (ProdI f g) = alg.prod (eval' alg f) (eval' alg g)

eval' alg Fst = alg.fst

eval' alg Snd = alg.snd

eval' alg (CoprodI f g) = alg.coprod (eval' alg f) (eval' alg g)

eval' alg InL = alg.left

eval' alg InR = alg.right

eval' alg Apply = alg.apply

eval' alg (Curry f) = alg.curry (eval' alg f)

eval' alg (Uncurry f) = alg.uncurry (eval' alg f) Overall, we can see that even as we've increased the complexity of the language, the structure of our evaluator has stayed the same. This is because at the core, an evaluator for an inductive type is nothing more than a homomorphism - a structure preserving map, whose behaviour is entirely determined by its actions on the generators of our algebraic theory.

And this is what makes the algebraic approach to programming so powerful. When we treat our language as an inductive type, we can reuse the same machinery we've developed for working with simpler algebraic structures such as monoids and semirings, but now apply it to more abstract structures, such as a typed combinator language for BCCs. As we will see through the course of this series, this scales to much more than just combinator languages, and even variable binding can be handled algebraically by working with inductive types over an appropriately chosen category.

In the next blog post we will have our first look at the simply typed lambda calculus and translate it into our combinator language, thus showing how to interpret the STLC into an arbitrary bicartesian closed category. After that, we'll start in earnest, and introduce the main tool we'll be using throughout the series - recursion schemes.